When Jonathan Ross and his wife Camilla Shivarg started househunting they had one main preoccupation: space. "Camilla is a painter and sculptor and I collect and show art," explains Jonathan. "We both work from home and have to have somewhere large enough not to run into each other during the day." The house they found - with its five generous floors - is, in fact, spacious enough to ensure that an entire department of civil servants could pursue their daily grind uninterrupted.

A white stucco-fronted mansion in Earl's Court, it is the sort of west London house that was built in the 19th century to accommodate the large nine-childrened households of the comfortably off Victorian middle class. But with the advent of contraception and the death of the servant classes, such houses were often converted into bedsits for backpackers. Fortunately for Jonathan and Camilla their house had been overlooked.

A white stucco-fronted mansion in Earl's Court, it is the sort of west London house that was built in the 19th century to accommodate the large nine-childrened households of the comfortably off Victorian middle class. But with the advent of contraception and the death of the servant classes, such houses were often converted into bedsits for backpackers. Fortunately for Jonathan and Camilla their house had been overlooked.

When they bought the property in 1997 it had been in the same family since before the First World War, retaining all of its original proportions and much of its quixotic details. It was, on the other hand, in that "you don't know what you're letting yourself in for" manner, unmodernised, and it took 18 months of concentrated renovation to bully it into a habitable state for 21st century life.

Today it is a modernised but not modern house. The denuded aesthetic of minimalism would never suit this artistic couple, and the rich flamboyance of the house's 19th-century roots is very much part of its charm. Jonathan and Camilla have used its reconditioned Victorian splendour as the perfect backdrop to their most definitely pre-modern passion for collecting and creating art.

"When I was a boy," explains Jonathan, "I had a museum and always wanted to invite people up to look at it. That's why I wanted a gallery in my home, because it's rather like having the grown-ups round to look at your collection."

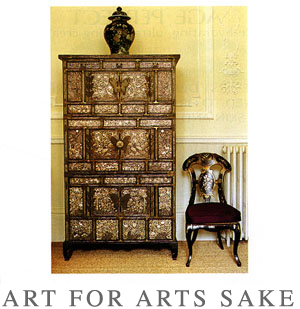

Even though Jonathan now has two designated gallery spaces - one white and clean in the basement, the other a rich Russian red in his ground floor dining room - his entire house might be deemed a very personal museum. Every available surface, horizontal and vertical, is ornamented with a collection of the curious, the artful, the bizarre and the beautiful. But his abiding passion is for holography, which he started collecting in the 1970s. "I get enormous pleasure from looking at images made of light. I must confess, I love the acquisitive aspect of owning artefacts from an early era of a developing art form."

He has holograms all over the house: in the hallway, on the shelves, in the cabinets. But it is in his basement showroom, with its specially adapted halogen lighting, that he remains the sole dealer of this luminous art form in Britain. "Some people used to have a private chapel attached to their house. But art is the new religion, so why not have an art gallery at home?" he says. Why not, indeed.

He has holograms all over the house: in the hallway, on the shelves, in the cabinets. But it is in his basement showroom, with its specially adapted halogen lighting, that he remains the sole dealer of this luminous art form in Britain. "Some people used to have a private chapel attached to their house. But art is the new religion, so why not have an art gallery at home?" he says. Why not, indeed.

Homes & Gardens Magazine,

January 2001.

Reproduced with permission.

Homes & Gardens feature

Production:

Gabi Tubbs.

Words:

Lisa Freedman.

Photographs:

Christopher Drake

Return to the features section or view,

The Evening Standard Magazine feature;

The Times Magazine feature.